| The exterior: description |

| The exterior: the facade |

| The outside: the bronze doors |

| The exterior: the mosaics of the external facade |

| The outside: the bezel |

| The exterior: the quadriga |

| The exterior: the Aquitaine pillars |

| The exterior: the stone of the ban |

| The outside: the tetrarchs |

| The outside: the narthex |

| The exterior: the narthex, dome of Genesis or Creation |

| The exterior: the narthex, the niches next to the portal |

| The mosaics: introduction |

| The mosaics: gold and inscriptions |

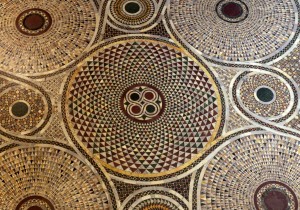

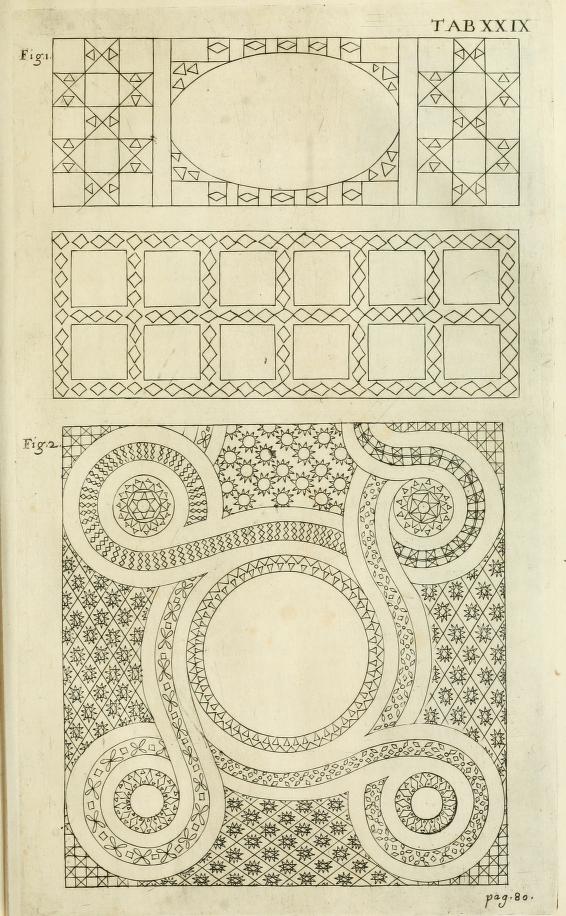

| The mosaics: opus tesselatum and opus sectile |

| The mosaics: the mosaics of the atrium |

| The mosaics: the mosaics of the north transept |

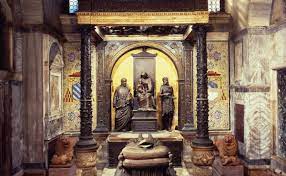

| The mosaics: the mosaics of the Zen Chapel |

| The mosaics: the authors of the cartoons |

| The mosaics: the masters and the origin |

| The mosaics: mosaics of the interior |

| The mosaics: the interior - the dome of the Presbytery |

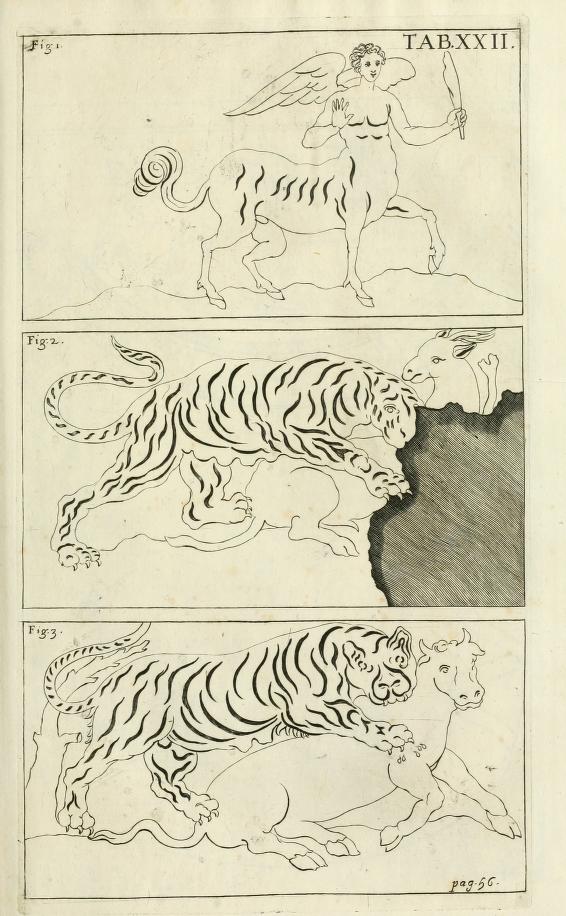

| The mosaics: the interior - the two transepts |

| The mosaics: the interior - the south and west vaults |

| The mosaics: the interior - the Oratory of the Garden |

| The mosaics: the interior - the Pentecost dome |

| The mosaics: the interior - the internal counter-façade |

| The mosaics: the interior - San Cesario, the saint against floods |